I attended the Smart Cities and Regions Summit in Croke Park, Dublin, today and took part in the ‘smart spaces and smart citizens?’ panel. We were asked to produce a short opening statement and thought I’d share it here.

I’m going to discuss smart citizens by considering Dublin as a smart city. To start, I want to ask you a set of questions which I’d like you to respond to by raising a hand. Don’t be shy; this requires participation.

How many of you have a good idea as to what Smart Dublin is and what it does?

How many of you feel you have a good sense of smart city developments taking place in Dublin?

Would you be able to tell me much about the 100+ smart city projects that are taking place in the city in conjunction with Smart Dublin and it four local authority partners?

Would you be able to tell me much about the extent to which these projects engage with citizens?

Or how the technologies used impact citizens, either in direct or implicit ways?

Or whether Smart Dublin and the four local authorities have a guiding set of principles or a programme for citizen engagement or smart citizens?

You’re all people interested in smart cities. You’re here because it relates to your work in some way. You have a vested interest in knowing about smart cities.

Do you think that citizens in Dublin know about these projects, which might be taking place in their locality?

Do you think that they have sufficient knowledge to be able judge, in an informed way, a project’s merits?

Do you think they have an active voice in these projects’ conception, their deployment, the work that they do? In how any data generated are processed, analysed, shared, stored, and value extracted, etc.?

Do local politicians – citizen representatives – know about them? And do they have an active voice in smart city development in Dublin?

This panel is titled ‘Smart spaces and smart citizens’.

What is difficult to see in most smart city initiatives is the ‘smart citizen’ element. It seems that what is implied by ‘smart citizen’ is simply being a person living in a city where smart city technology is deployed, or being a person that uses networked digital technology as part of everyday life.

To create a smart citizen, all a state body or company apparently needs to do is say people should be at the heart of things, or enact a form of stewardship (deliver a service on behalf of citizens) and civic paternalism (decide what’s best for citizens), rather than citizens being meaningfully involved in the vision and development of the smart city.

In our own research concerning networked urbanism and smart cities from a social sciences perspective we have been interested in exploring these kinds of questions, and how the citizen fits into the smart city. It’s a central concern in our latest book published next month, ‘The Right to the Smart City’, which explores the smart city in relation to notions of citizenship and social justice.

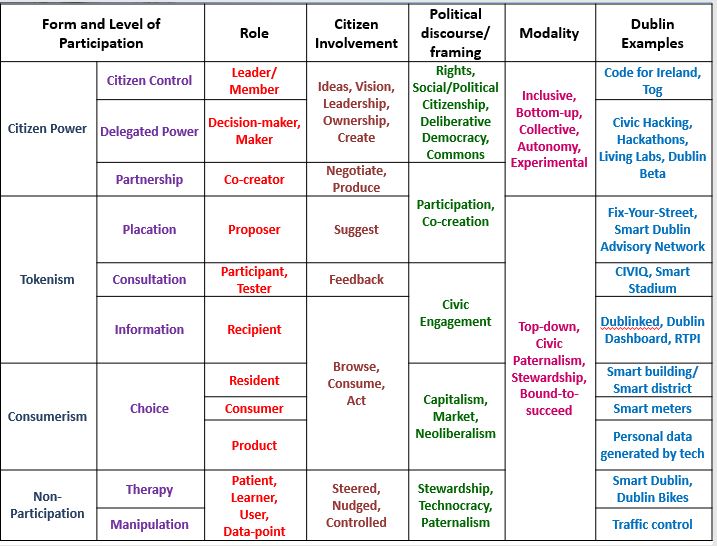

What our research shows is that citizens can be varyingly positioned, and perform very different roles, in the smart city depending on the type of initiative.

It is perhaps no surprise then that citizens in numerous jurisdictions have started to push back against the more technocratic, top-down, marketised versions of the smart city – the on-going protests in Toronto over the Sidewalk Labs waterfront development being a prominent example. Instead, they demand more inclusive, empowering and democratic visions, with Barcelona’s notion of technological sovereignty often providing inspiration (see my recent piece comparing Toronto and Barcelona and links to articles and organisation websites).

It is difficult to argue that we are enabling ‘smart citizens’ if they are not informed, consulted or involved in the development and roll-out of smart city initiatives. As such, if we are truly interested in creating smart citizens then we need to make a meaningful move beyond the dominant tropes of stewardship and civic paternalism to approach smart cities in a smarter way.

For a fuller discussion see the opening and closing chapters of The Right to the Smart City, which are available as open access versions.

Kitchin, R., Cardullo, P. and di Feliciantonio, C. (2018) Citizenship, Social Justice and the Right to the Smart City. Pre-print Chapter 1 in The Right to the Smart City edited by Cardullo, P., di Feliciantonio, C. and Kitchin, R. Emerald, Bingley.

Kitchin, R. (2018) Towards a genuinely humanizing smart urbanism. Pre-print Chapter 14 in The Right to the Smart City edited by Cardullo, P., di Feliciantonio, C. and Kitchin, R. Emerald, Bingley.

Rob Kitchin