This afternoon’s black cab blockade of London comes in response to car ride apps that are changing the character of the city’s taxi industry. While there has been little visible backlash against comparable services in Ireland, it seems only a matter of time before these struggles find their way to our shores.

The market-leading smart phone taxi service in Ireland is Hailo. Self-described as “the evolution of the hail”, Hailo was founded in November 2011 by three London taxi drivers and three entrepreneurs. It launched in Dublin, its second city, in July 2012 and as of mid-2014, provides sporadic coverage across the country with a specific attention on areas of high population density.

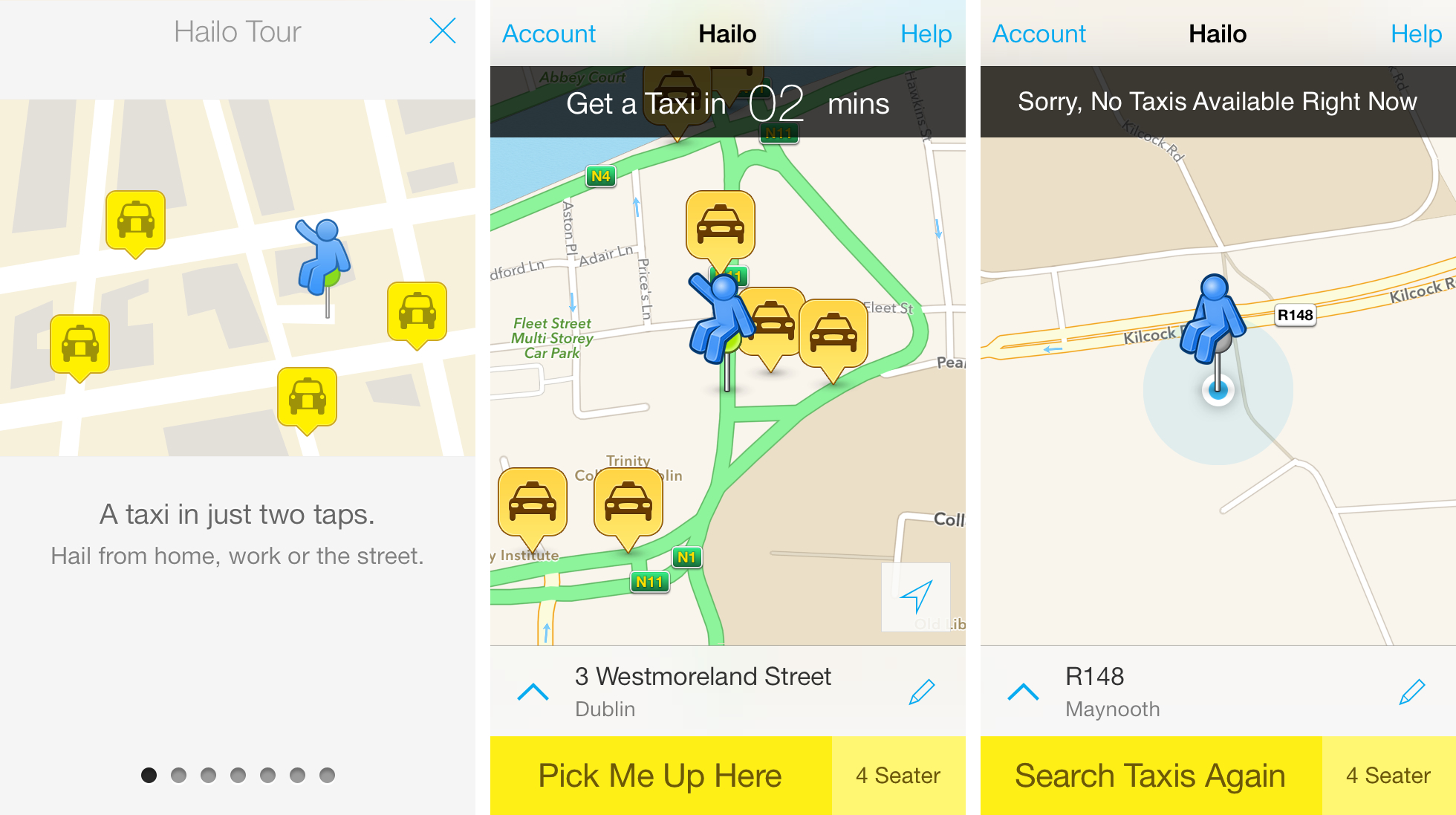

To use Hailo as a potential passenger, one needs simply to download and launch their free smart phone application. To use the Hailo as a driver, things are a little more complicated. One must sign up using a geographically specific online portal (such as exists for London, Ireland, New York, Boston and Tokyo). Registration is restricted to licensed taxi drivers such that Hailo is effectively leveraging the screening procedures of existing small public service vehicle (SPSV) infrastructure in Ireland. Of Dublin’s 12,000 registered taxi drivers, I’ve been told that about half are using the service.

In this post I will describe two observations on the role Hailo plays in Dublin: that it competes with existing taxi infrastructure, and that it capitalises on and potentially extends the deregulation of transportation in the city. I will briefly compare the service to Uber and Lyft, and argue why their competition will likely bring the taxi wars to Dublin.

Hailo competes with existing taxi infrastructure

In addition to plying for hire (being in motion and available for hire) and standing for hire (being stationary and available for hire), taxi drivers can increase their number of fares by enrolling to a radio service. When a customer phones a taxi company, this company then leverages its radio-enabled network to source an available taxi driver. Cab drivers working in Dublin have told me that subscription to such a service can cost as much as €5,000 per year. This service is dependent upon a radio communications unit being physically installed into driver’s vehicle, the hire of which is presumably incorporated into the cost of the service.

Hailo, in drawing upon already existing smart phone usage, does not need to install any radio communications infrastructure. This means lower fixed capital costs and lower associated installation and maintenance costs. Furthermore, by having software perform the role of the radio operator, there are presumably fewer attendant labour costs.

These factors lead to a considerably different pricing model. Rather than charge a yearly subscription fee, Hailo is free to install and use, but charges a 12% commission on every fare sourced through the application. In order to compete with these rates, a €5,000 per year radio service would need to direct €41,667 worth of fares to each driver. Understandably, Hailo poses a considerable threat to Dublin’s taxi radio companies.

There is however an important geographical caveat which needs to be made. In cities such as Dublin – where there is a confluence of high population density, a high number of taxis per head and a high usage of smart phones – the benefits of Hailo to both drivers and passengers outweigh those offered by taxi radio companies. In a geographical location where taxi or smart phone use is more sparsely distributed however, Hailo has less opportunity to draw upon existing infrastructure. Where I work in Maynooth – a small university town 20 kilometres west of Dublin – it is very difficult to find a taxi using Hailo. In such locations both spatial scarcity and community loyalty lead me to suppose far less competition between Hailo and existing taxi radio services. In these instances, the volume of jobs rather than rate of commission is the important factor.

Competing SPSV smart phone service Uber, which has been recently valued at a truly astounding $18.2bn1, launched in Dublin in January 2014. Uber operates under a business model which is far more challenging to existing taxi infrastructures as a whole. Rather than recruit taxi drivers exclusively, Uber is open to private hire vehicle (or limousine) drivers as well. Less regulation on the cost of limousine services allows the company to employ a surge pricing model, so that fares can cost considerably more than a standard rate (up to as much as eight times more expensive in rare incidences of peak demand). The cost of an SPSV licence for limousines in Ireland is only €250, compared to the €6,300 for a taxi licence. While cars must still be deemed as fit for such a purpose, and drivers must similarly undergo clearance by An Garda Síochána, Uber hopes that its matchmaking infrastructure for limousine services will allow its service to compete favourably with the taxi industry as a whole. It’s probably too soon to draw any conclusions on the success of the company in Dublin, but you can be sure they are here for the long run. Uber have money to burn and their CEO Travis Kalanick has a combative attitude toward vested interests.

Hailo capitalises on and potentially extends the deregulation of transportation in the city

As described above Hailo is most effective in urban areas where there is already considerable competition amongst taxi drivers. Uptake amongst drivers is dependent upon a pull effect, whereby not using the service would render them excluded from a proportion of the passenger market. There is, as such, a supply-and-demand-like positive feedback loop between the driver and passenger applications. Increased use of the application by one group would be expected to result in an increase in use by the other.

It was not always so easy to hail a taxi in Dublin. Between 1978 and 2000 local authorities in Ireland were entitled to limit the number of taxi licences issued in their area. In Dublin, the number of licences in circulation between 1978 and 1988 was fixed at 1,800. This number was increased slowly through the late 1980s and 1990s to around 2,800 by the end of the decade. Supply was not kept up with demand however. By the late 1990s the cost of purchasing a licence on the open market was as much as €100,000. In line with its commitment to improving Dublin’s taxi services, the Action Programme for the Millennium encouraged the issuance of 3,100 new licences in the city in November 1999. This was not found to be enough however, as one year later, on November 21, 2000, S.I No. 367/20002 lifted licensing regulations in Ireland. This had the immediate effect of devaluing existing licences and subsequent enquiries and legal cases have been undertaken to assess the fairness of this deregulation. The change has had its intended effect however. By 2008, union estimates placed the number of taxi licences nationwide at 19,000 with 12,000 of those being held in Dublin. Locals tell me that these days it is much easier to get a cab home after a night out than it was in the 1990s.

Under conditions where taxi drivers do not have to compete so vigorously for fares (under a licence-restricted, consortium-based or heavily unionised model rather than the predominantly individualised system currently in operation in Ireland), there would be little pressure for them to use Hailo. And as I’ve already argued, no drivers using the service would translate to no passengers using it either. Indeed it is quite clear from various interviews and media appearances that Hailo have made tactical decisions about how and in which cities they introduce their service.

While Hailo takes advantage of such spaces of deregulation, it has been careful so far to adhere to local legislation. The service does not on its own necessitate a further deregulation of the SPSV sector in Ireland. Hailo is not unique however. Competitors include the globe-spanning Uber, Lyft, Sidecar, Wingz, Summon and Flywheel in the USA, cab:app, Cab4Now, Get Taxi and Kabbee in London and Chauffeur-Privé in France. These transportation network companies compete on a range of business models, services and geographical coverage. This marketplace of competing car ride apps has the potential to push against regulations which are in place to control regional SPSV sectors in Ireland.

Consider the following examples from what’s been called the taxi wars.

Since March 2014, Republican Senator Marco Rubio has been pushing for the deregulation of the limousine industry in Miami, Florida specifically to make way for the introduction of Uber. The taxi and limousine industry in Miami-Dade county is strongly regulated. The industry caters to a population of over 2,500,000 people through 2,121 taxi medallions (which is the equivalence of a vehicle licence in Ireland). This has forced the market price of a medallion to around $340,000, 28% of which are owned by taxi drivers. Similarly, limousines licences are limited to 625 in number. Services must be booked an hour in advance with rides costing a minimum of $70. This regulation is directly restrictive of Uber’s business model. After Senator Rubio’s efforts to clear the company’s way stalled, actor Ashton Kutcher was recruited to tackle regulation from a different front, decrying the city’s bizarre, old, antiquated legislation” on Jimmy Kimmel Live. On May 22 rival company Lyft – “your friend with a car”, which adopts a decentralised ride sharing model – launched in Miami on a donation-based payment scheme. This forced a response by Uber, which launched its comparably modelled UberX service in the city on June 4. These are not isolated events. Similar changes are being forced on other regions of the US such as: Arlington, Virginia; San Antonio, California; and Austin, Texas.

Uber arrived in London, it’s first European city, in mid-2012. London’s taxi industry consists of over 25,000 hackney carriage taxis serving a daytime population of around 10,000,000. In order to obtain a taxi licence, or Green Badge, drivers must pass to a knowledge test covering a 113 square mile area of the city which is purported to require up to five years of study. Uber, in accepting any driver with a private hire vehicle licence, poses a clear threat to the time and money that London’s taxi drivers have invested in their profession. In recent weeks, The Licensed Taxi Drivers Association has summoned six Uber drivers to court, alleging that the Uber smartphone app is equivalent to a taximeter and therefore illegal under the 1998 Private Hire Act which reserves that right for licensed taxi drivers. In addition, the London taxi-driver’s union lambast Transport for London for failing to pursue the illegal activities which Uber facilitate, suggesting that the state body is afraid of the money backing Uber. In response, Transport for London has sought a binding decision from the high court regarding the legality of the smart phone taximeter.

The way in which other transportation network companies have responded to Uber’s entrance into the London market is important in the case of Ireland. Hailo have announced that they will extend their services to private hire vehicles in addition to taxis. This was news was not well accepted by the industry, with the word ‘scabs’ being gratified on the wall of Hailo’s London office. The company responded on their website, insisting that they are simply following consumer demand. Assuming the move doesn’t too badly damage its position among existing service users, we can expect to see something similar in Ireland, either to pre-empt or combat Uber’s growing market share. Not all apps are going the way of private vehicle hire however. Competitor Cab:app has pushed back against the trend set by Uber and Hailo, asserting publicly its commitment to the taxi industry.

Protests in London and throughout Europe today (June 11, 2014) are in direct opposition to Uber’s perceived infringement upon the taxi industry. In the past, strike action has escalated to involve the destruction of property. In January 2014, Parisian taxi drivers struck in opposition to Uber’s unregulated market competition. Confrontations between unionised taxi drivers and Uber drivers resulted in “Smashed windows, tires, vandalized vehicle[s], and bleeding hands”.

The Irish SPSV sector is admittedly quite different from comparable industries in America, the UK and France. Hailo does not face the same kind of regulatory barriers in Ireland as it would in parts of the US. The National Taxi Drivers’ Union is less powerful than taxi unions in London, and certainly less militant than those in Paris. Hailo is a relatively well behaved company in this sector however. As competitors such as Uber and Lyft seek to expand their more aggressive strategies throughout Europe, it is highly likely, given the success of Hailo and Dublin’s reputation as a high-tech-friendly city, that a real push will be made to establish a foothold in Ireland. Spokesperson for Uber’s international operations Anthony El-Khoury has told the Irish Times: “We see a lot of potential in the Irish market and a lot of demand”. As this market heats up, pressure to further deregulate the SPSV industry will be put on Dublin City Council and the Irish government.

The future of the SPSV sector in Ireland

These two preliminary observations on the role of Hailo in Dublin are commensurate with larger tendencies of state deregulation and market-oriented competition. While the emergence of car ride apps may be positioned as a form of Schumpeterian creative-destruction, there are larger political and economic forces within which these applications should be contextualised. I have attempted to sketch some of these forces in this blog post.

The taxi industry is regulated for a reason. The screening and approval of drivers is important in ensuring accountability and the safety of passengers. Regular metering and Ireland’s nationwide fare system (which was instituted in September 2006) make certain that taxis provide an honest and consistent service that does not gouge rural communities or those in need. While Hailo operates under a minimally challenging model to these standards, it does not exist in a vacuum. By exploiting the freer regulation of limousines, Uber is effectively side-stepping many but not all of them. By doing away with accreditation altogether, Lyft would throw these standards onto the wills of the market. Car ride apps have the potential to put huge pressure on the taxi and limousine business. If other European cities are anything to go by Ireland’s SPSV sector is likely to be forced to deregulate further in coming years. This impacts the price, availability and safety of taxi services, and undercuts the ability of workers in the industry to bargain for fair pay and work conditions. It is important that any changes to the sector be submitted to proper public scrutiny and debate.

Updates

June 12 – An article on RTE alerted me to the recent launch of Wundercar in Dublin. The app seems to follow the Lyft or UberX business model, whereby unlicensed drivers give passengers a lift somewhere in the city for “tips”. Drivers are screened by Wundercar rather than An Garda Síochána.

June 22 – The Independent reported on June 20 that Hailo is offering a suite of new services targeting the business sector. Most significant to my discussion here is the introduction of the company’s limousine option to Ireland. Limousine licences are considerably cheaper than taxi licences and there are fewer regulations on fare pricing.

Aswath Damodaran of New York University claims that a more accurate valuation would be around $6bn. By way of comparison Hailo was valued, 18 months ago, at a far more modest $140m.↩

Also called Road Traffic (Public Service Vehicles) (Amendment) (No. 3) Regulations 2000.↩