Up until relatively recently tracking the location and movement of individuals was a slow, labour-intensive, partial and difficult process. The only way to spatially track an individual was to follow them in person and to quiz those with whom they interacted. As a result, people’s movement was undocumented unless there was a specific reason to focus on them through the deployment of costly resources. Even if a person was tracked, the records tended to be partial, bulky, difficult to cross-tabulate, aggregate and analyze, and expensive to store.

A range of new technologies has transformed geo-location tracking to a situation where the monitoring of location is pervasive, continuous, automatic and relatively cheap, it is straightforward to process and store data, and easy to build up travel profiles and histories. This is especially the case in cities, where these technologies are mostly deployed, though some operate pretty much everywhere. Here are eleven (updated from 7 in original post) examples.

1. Many cities are saturated with remote controllable digital CCTV cameras that can zoom, move and track individual pedestrians. In addition, large parts of the road network and the movement of vehicles are surveyed by traffic, red-light, congestion and toll cameras. Analysis and interpretation of CCTV footage is increasingly aided by facial, gait and automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) using machine vision algorithms. Several police forces in cities in the UK have rolled out CCTV facial recognition programmes (1,2), as have cities in the U.S., including New York and Chicago (each with over 24,000 cameras) and San Diego (who are also using smartphones with facial recognition installed) (3). ANPR cameras are installed in many cities for monitoring traffic flow, but also for administrating traffic violations such as the non-payment of road tolls and congestion charging. There are an estimated 8,300 ANPR cameras across the UK capturing 30 million number plates each day (15).

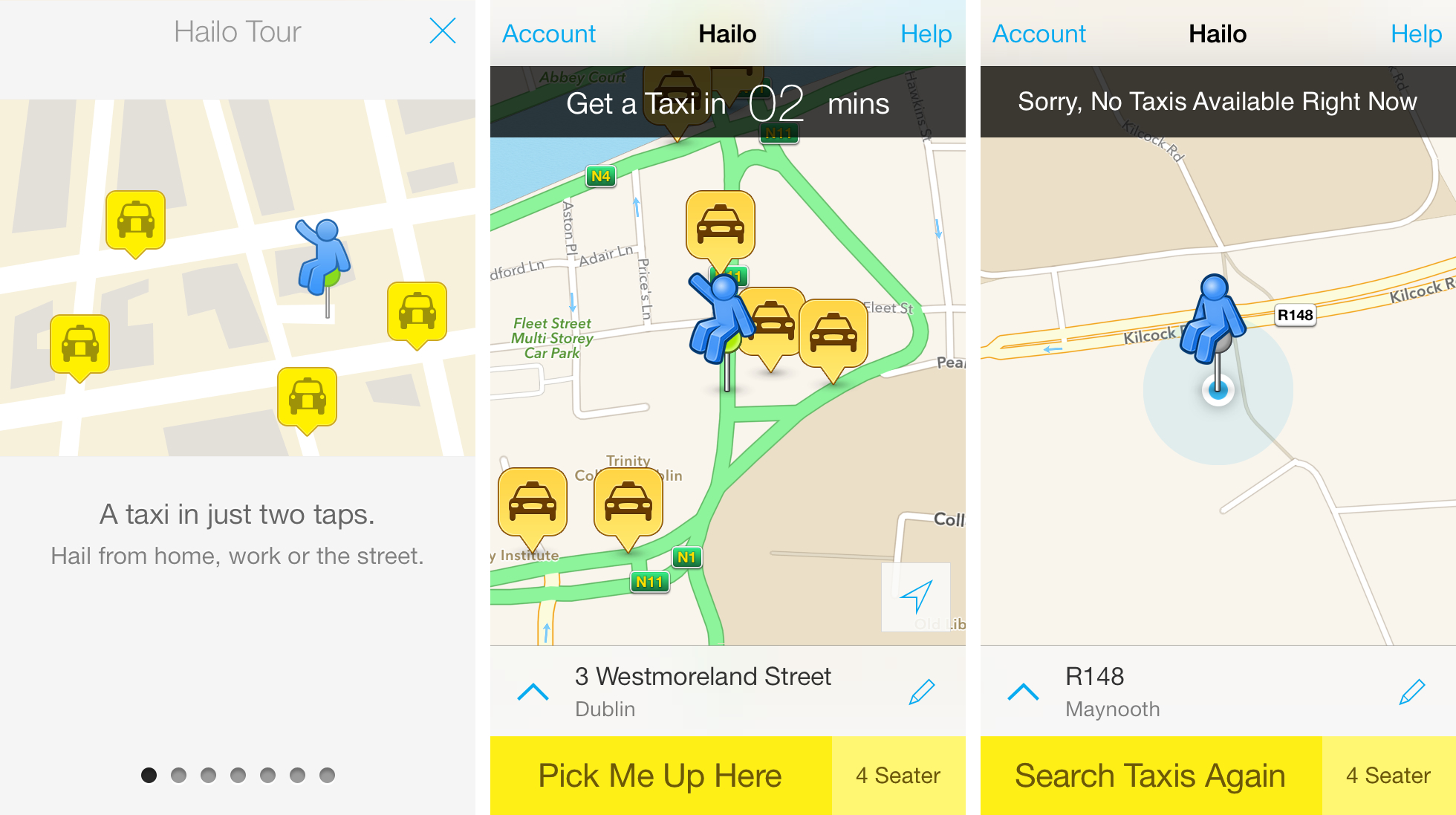

2. Smart phones continuously communicate their location to telecommunications providers, either through the cell masts they connect to, or the sending of GPS coordinates, or their connections to wifi hotspots. Likewise, smart phone apps can access and transfer such information and also share them to third parties. With respect to the latter Leszczynski’s analysis (14) of the data generated by The Wall Street Journal in 2011 (4) details that 25 out 50 iPhone apps, and 21 of 50 Android apps transmitted location data to a third party other than the app developer. Of these, 19 of the iPhone apps and 13 of the Android apps did not require locational data as a functional requirement. Half the iPhone and a third of the Android apps did not request consent for passing on the locational data. These locational data are shared with advertisers and utilised by data brokers to create user profiles. For example, ‘Verizon have a product called Precision Market Insights that let businesses track cell phone users in particular locations’ (5). It sells data ‘about its cell phone users’ “age range, gender and zip codes for where they live, work, shop and more” as well as information about mobile-device habits’ including URL visits, app downloads and usage, browsing trends and more’ (5).

3. In a number of cities sensor networks have been deployed across street infrastructure such as bins and lampposts to capture and track phone identifiers such as MAC addresses. In London, Renew installed such sensors on 200 bins, capturing in a single week in 2014 identifiers from 4,009,676 devices and tracking these as they moved from bin to bin (6). The company reported that they could measure the proximity, speed, and manufacturer of a device and track the stores individuals visited, how long they stayed there, and how loyal customers are to particular shops, using the information to show contextual adverts on LCD screens installed on the bins (6). The same technology is also used within malls and shops to track shoppers, sometimes linking with CCTV to capture basic demographic information such as age and gender (7, 8).

4. Similarly, some cities have installed a wifi mesh, either to provide public wifi or to create a privileged emergency response and relief communication system in the event of an urban disaster or for general surveillance. In the case of public wifi the IDs of the devices which access the networked are captured and can be tracked between wifi points. In the case of an emergency/police mesh access might not be granted to the network, however each network access point can capture the device IDs, device type, apps installed, as well as the locational history (9). Such a wifi mesh, with 160 nodes, was installed by the Seattle Police Department in 2013 (9). The locational history of previous wifi access points is revealed because a wifi-enabled device broadcasts the name of every network it has connected to previously in order to try and find one it can connect to automatically. Such data reveals the movement of device owners between locations, revealing the sites of popular spots such as home, work, and where they shop. Beyond a wifi-mesh, anyone with a wi-fi adapter in monitor mode and a packet capture utility can capture such data (12).

5. Many buildings use smart card tracking, with unique identifiers installed either through barcodes or embedded RFID chips. Cards are used for access control to different parts of the building and to register attendance, but can also be used as an electronic purse to pay for items within the facility. Smart card tracking is becoming increasingly common in many schools to track and trace student movements, activities and food consumption (10). Smart cards are also used to access and pay for public transport, such as the Leapcard in Dublin or the Oyster Card in London. Each reading of the card adds to the database of movement within a campus or across a city.

6. New vehicles are routinely fitted with GPS that enables the on-board computers to track location, movement, and speed. These devices can be passive and store data locally to be downloaded for analysis at a latter point, or be active, communicating in real-time via cellular or satellite networks to another device or data centre. Active GPS tracking is commonly used in fleet management to track goods vehicles, public transport and hire cars, or to monitor cars on a payment plan to ensure that it can be traced and recovered in cases of default, or in private cars as a means of theft recovery. Moreover, cars are increasingly being fitted with unique ID transponders that are used for the automated operation and payment of road tolls and car parking. Again, each use of the transponder is logged, creating a movement data trail, though with a larger spatial and temporal granularity (at selected locations).

7. There are also many other staging points where we might leave an occasional trace of our movement and activities, such as using ATMs, or a credit card in a store, or checking a book out of a library.

UPDATE: I’ve had three further ways of tracking people pointed out to me (thanks Linda, Stephen, Jim) and I also thought of one more. Plus I’ve updated method 4 (thanks Paul-Olivier).

8. Selected populations — such as people on probation, prisoners on home leave, people with dementia, children — are being electronically tagged to enable tracking. Typically this done using a GPS-enabled bracelet that periodically transmits location and status information via a wireless telephone network to a monitoring system. In other cases, it is possible to install tracker apps onto a phone (of say children) so the phone location can be tracked, or to buy a family tracking service from telecoms providers (11)

9. Another form of staging point is the use of the Internet, such as browsing or sending email, where the IP address of the computer reveals the approximate location from which it is connected. Typically this does not have a fine spatial resolution (mile to city or region scale), but does show sizable shifts of location between places.

10. Another set of staging points can be revealed from the geotagging (using the device GPS) and time/date stamping of photos and social media posted on the internet and recorded in their associated metadata. This has more spatial resolution than IP addresses and is also accompanied with other contextual information such as the content of the photo/post. Such data can be used in interesting ways such as tackling cyber-bullying by revealing the location of posters (13).

11. Location and movement can also be voluntarily shared by individuals through online calenders, most of which are private but nonetheless stored in the cloud, and some of which are shared openly or with colleagues.

As these examples demonstrate, those companies and agencies who run these technologies possess a vast quantity of highly detailed spatial behaviour data from which lots of other insights can be inferred (such as mode of travel, activity, and lifestyle). These data can also be shared between data brokers and third parties and combined with other personal and contextual information. For example, Angwin (5) has identified 58 data brokers in the mobile and location tracking business in the US, only 11 of which offered opt-outs (in total she found 212 data brokers operating in the US that consolidated and traded data about people, only 92 of which allowed opt-outs – 65 of which required handing over additional data to secure the opt-out). Moreover, these data can be accessed by the police and security forces through warrants or more surreptitiously. The consequence is that individuals are no longer lost in the crowd, but rather they are being tracked and traced at different scales of spatial and temporal resolution, and are increasingly becoming open to geo-targeted profiling for advertising and social sorting.

If you can think of other ways location/mobility is being tracked, please leave a comment – thanks.

Rob Kitchin

(1) Graham, S. (2011) Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism. Verso, London.

(2) Gardham, M. (2015) Controversial face recognition software is being used by Police Scotland, the force confirms. Herald Scotland, 26th May http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13215304.Controversial_face_recognition_software_is_being_used_by_Police_Scotland__the_force_confirms/

(3) Wellman, T. (2015) Facial Recognition Software Moves From Overseas Wars to Local Police. New York Times, 12th August. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/13/us/facial-recognition-software-moves-from-overseas-wars-to-local-police.html

(4) http://blogs.wsj.com/wtk-mobile/

(5) Angwin, J. (2014) Dragnet Nation. St Martin’s Press, New York

(6) Vincent, J. (2014) London’s bins are tracking your smartphone. The Independent. June 10th http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/updated-londons-bins-are-tracking-your-smartphone-8754924.html

(7) Kopytoff, V. (2013) Stores Sniff Out Smartphones to Follow Shoppers, Technology Review, Nov 12th http://www.technologyreview.com/news/520811/stores-sniff-out-smartphones-to-follow-shoppers/

(8) Henry, A. (2013) How Retail Stores Track You Using Your Smartphone (and How to Stop It). Lifehacker, 19 July, http://lifehacker.com/how-retail-stores-track-you-using-your-smartphone-and-827512308

(9) Hamm, D. (2013) Seattle police have a wireless network that can track your every move. Kirotv.com, 23 November. http://www.kirotv.com/news/news/seattle-police-have-wireless-network-can-track-you/nbmHW/ cited in Leszczynski, A. (forthcoming) Geoprivacy. In Kitchin, R., Lauriault, T. And Wilson, M. (eds) Understanding Spatial Media. Sage, London.

(10) Goodman, M. (2015) Future Crimes: A Journey to the Dark Side of Technology – and How to Survive It. Bantam Press, New York.

(11) see http://gizmodo.com/how-to-stalk-a-cheater-using-satellites-and-cell-phones-1546627447

(12) Gallagher, S. (2014) Where’ve you been? Your smartphone’s Wi-Fi is telling everyone. Ars Technica, Nov 5th, http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2014/11/where-have-you-been-your-smartphones-wi-fi-is-telling-everyone/

(13) Riotta, C. (2015) How Facebook and Twitter Geotagging Is Exposing Racist Trolls in Real Life. Tech.mic, Dec 2nd, http://mic.com/articles/129506/how-facebook-and-twitter-geotagging-is-exposing-racist-trolls-in-real-life

(14) Leszczynski, A. (forthcoming) Geoprivacy. In Kitchin, R., Lauriault, T. And Wilson, M. (eds) Understanding Spatial Media. Sage, London.

(15) Weaver, M. (2015) Warning of backlash over car number plate camera network. The Guardian, 27 Nov. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/nov/26/warning-of-outcry-over-car-numberplate-camera-network