Rob Kitchin provides the first interview in a new series on the LSE Impact blog entitled ‘Big Data, Big Questions’ curated by Mark Carrigan. The post concerns the philosophy of data science, the nature of ‘big data’, the opportunities and challenges presented for scholarship with its growing influence, the hype and hubris surrounding its advent, and the distinction between data-driven science and empiricism. You can read more over at the LSE Impact blog.

Author Archives: Rob Kitchin

New paper: Big data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts

Rob Kitchin’s paper ‘Big data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts’ has been published in the first edition of a new journal, Big Data and Society, published by Sage. The paper is open access and can be downloaded by clicking here. A video abstract is below. The paper is also accompanied by a blog post ‘Is big data going to radically transform how knowledge is produced across all disciplines of the academy?’ on the Big Data and Society blog.

Abstract

This article examines how the availability of Big Data, coupled with new data analytics, challenges established epistemologies across the sciences, social sciences and humanities, and assesses the extent to which they are engendering paradigm shifts across multiple disciplines. In particular, it critically explores new forms of empiricism that declare ‘the end of theory’, the creation of data-driven rather than knowledge-driven science, and the development of digital humanities and computational social sciences that propose radically different ways to make sense of culture, history, economy and society. It is argued that: (1) Big Data and new data analytics are disruptive innovations which are reconfiguring in many instances how research is conducted; and (2) there is an urgent need for wider critical reflection within the academy on the epistemological implications of the unfolding data revolution, a task that has barely begun to be tackled despite the rapid changes in research practices presently taking place. After critically reviewing emerging epistemological positions, it is contended that a potentially fruitful approach would be the development of a situated, reflexive and contextually nuanced epistemology.

Workshop: Code and the City, 3-4 September

In early September the Programmable City project at NUI Maynooth will be hosting a number of the foremost thinkers on the intersection of software, ubiquitous computing and the city for a two day workshop entitled ‘Code and the City’.

We’re really excited to be gathering together these scholars to discuss their ideas and research. We’ve structured the programme so that each session lasts for two hours, with c. an hour for presentations, followed by an hour of discussion and debate. Full draft written papers will be circulated in advance to attendees.

To try and make sure the event operates as a workshop we are limiting the numbers attending to the speakers, plus our team, plus a handful of open slots. If you are interested in attending then please email Sung-Yueh.Perng@nuim.ie with your request by June 6th, setting out why you would like to attend. We will then allocate the additional places by June 13th.

Introduction

Code and the City

Rob Kitchin, NIRSA, National University of Ireland Maynooth

Session 1: Automation/algorithms

Cities in code: how software repositories express urban life

Adrian Mackenzie, Sociology, Lancaster University

Autonomy and automation in the coded city

Sam Kinsley, Geography, University of Exeter

Interfacing Urban Intelligence

Shannon Mattern, Media Studies, New School NY

Session 2: Abstraction and urbanisation

Encountering the city at hackathons

Sophia Maalsen and Sung-Yueh Perng, National University of Ireland, Maynooth

Disclosing Disaster? A Study of Ethics, Praxeology and Phenomenology in a Mobile World

Monika Büscher, With Michael Liegl, Katrina Petersen, Mobilities.Lab, Lancaster University, UK

Riot’s Ratio, on the genealogy of agent-based modeling and the cities of civil war

Matthew Fuller and Graham Harwood, Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths

Session 3: Social/locative media

Digital social interactions in the city: Reflecting on location-based social media

Luigina Ciolfi, Human-Centred Computing, Sheffield Hallam University

A Window, a Message, or a Medium? Learning about cities from Instagram

Lev Manovich, Computer Science, The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Feeling place in the city: strange ontologies, Foursquare and location-based social media

Leighton Evans, National University of Ireland Maynooth

Mobility in the actually existing smart city: Developing a multilayered model for the mobile computing dispositif

Jim Merricks White, National University of Ireland, Maynooth

Session 4: Knowledge classification and ontology

Cities and Context: The Codification of Small Areas through Geodemographic Classification

Alex Singleton, Geography, University of Liverpool

The city and the Feudal Internet: Examining Institutional Materialities

Paul Dourish, Informatics, UC Irvine

From Jerusalem to Kansas City: New geopolitics and the Semantic Web

Heather Ford and Mark Graham, Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford

Session 5: Governance

From community access to community calculation: exploring alternative urban governance through code

Alison Powell, Media & Communications, LSE

Code and the socio-spatial stratification of the city

Agnieszka Leszczynski, Geography, University of Birmingham

The Cryptographic City

David M. Berry, Media & Communication, University of Sussex

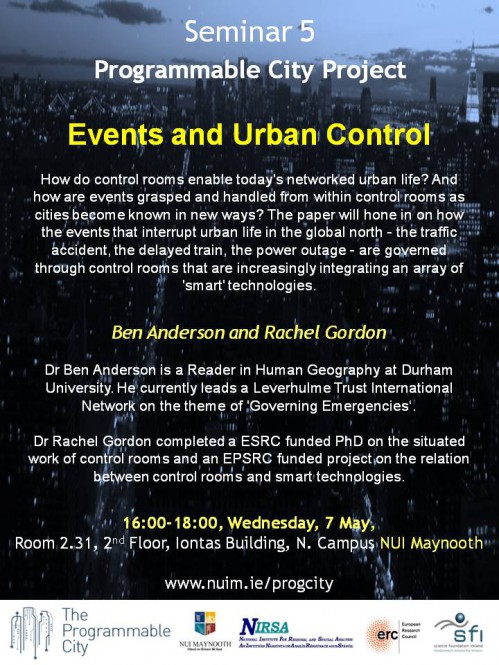

Seminar: Events and Urban Control by Ben Anderson and Rachel Gordon, 7 May

The fifth Programmable City seminar will take place on May 7th. Based on some detailed ethnographic work, the paper will focus on the workings of control rooms in governing events.

Events and Urban Control

Ben Anderson and Rachel Gordon

Time: 16:00 – 18:00, Wednesday, 7 May, 2014

Venue: Room 2.31, 2nd Floor Iontas Building, North Campus NUI Maynooth (Map)

Abstract

How do control rooms enable today’s networked urban life? And how are events grasped and handled from within control rooms as cities become known in new ways? The paper will hone in on how the events that interrupt urban life in the global north – the traffic accident, the delayed train, the power outage – are governed through control rooms; control rooms that are increasingly integrating an array of ‘smart’ technologies. Control rooms are sites for detecting and diagnosing events, where action to manage events is initiated in the midst multiple forms of ambiguity and uncertainty. By focusing on the work of control rooms, the paper will ask what counts as an event of interruption or disruption and trace how forms of control are enacted.

About the speakers

Dr Ben Anderson is a Reader in Human Geography at Durham University. Recently, he has become fascinated by how emergencies are governed and how emergencies govern. He currently leads a Leverhulme Trust International Network on the theme of ‘Governing Emergencies’, and is conducting a geneaology of the government of and by emergency supported by a 2012 Philip Leverhulme Prize. Previous research has explored the implications of theories of affect and emotion for contemporary human geography. This work will be published in a monograph in 2014: Encountering Affect: Capacities, Apparatuses, Conditions (Ashgate, Aldershot). He is also co-editor (with Dr Paul Harrison) of Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography (2010, Ashgate, Aldershot).

Dr Rachel Gordon completed a ESRC-Funded PhD on the situated work of control rooms, with particular reference to transport systems and to how control rooms deal with complex urban systems. She currently coordinates an Leverhulme Trust international network on Governing Emergencies, after completing an EPSRC funded project on the relation between control rooms and smart technologies.

Writing for impact: how to craft papers that will be cited

For the past few years I’ve co-taught a professional development course for doctoral students on completing a thesis, getting a job, and publishing. The course draws liberally on a book I co-wrote with the late Duncan Fuller entitled, The Academics’ Guide to Publishing. One thing we did not really cover in the book was how to write and place pieces that have impact, rather providing more general advice about getting through the peer review process.

The general careers advice mantra of academia is now ‘publish or perish’. Often what is published and its utility and value can be somewhat overlooked — if a piece got published it is assumed it must have some inherent value. And yet a common observation is that most journal articles seem to be barely read, let alone cited.

Both authors and editors want to publish material that is both read and cited, so what is required to produce work that editors are delighted to accept and readers find so useful that they want to cite in their own work?

A taxonomy of publishing impact

The way I try and explain impact to early career scholars is through a discussion of writing and publishing a paper on airport security (see Figure 1). Written pieces of work, I argue, generally fall into one of four categories, with the impact of the piece rising as one traverses from Level 1 to Level 4.

Level 1: the piece is basically empiricist in nature and makes little use of theory. For example, I could write an article that provides a very detailed description of security in an airport and how it works in practice. This might be interesting, but would add little to established knowledge about how airport security works or how to make sense of it. Generally, such papers appear in trade magazines or national level journals and are rarely cited.

Level 2: the paper uses established theory to make sense of a phenomena. For example, I could use Foucault’s theories of disciplining, surveillance and biopolitics to explain how airport security works to create docile bodies that passively submit to enhanced screening measures. Here, I am applying a theoretical frame that might provide a fresh perspective on a phenomena if it has not been previously applied. I am not, however, providing new theoretical or methodological tools but drawing on established ones. As a consequence, the piece has limited utility, essentially constrained to those interested in airport security, and might be accepted in a low-ranking international journal.

Level 3: the paper extends/reworks established theory to make sense of phenomena. For example, I might argue that since the 1970s when Foucault was formulating his ideas there has been a radical shift in the technologies of surveillance from disciplining systems to capture systems that actively reshape behaviour. As such, Foucault’s ideas of governance need to be reworked or extended to adequately account for new algorithmic forms of regulating passengers and workers. My article could provide such a reworking, building on Foucault’s initial ideas to provide new theoretical tools that others can apply to their own case material. Such a piece will get accepted into high-ranking international journals due to its wider utility.

Level 4: uses the study of a phenomena to rethink a meta-concept or proposes a radically reworked or new theory. Here, the focus of attention shifts from how best to make sense of airport security to the meta-concept of governance, using the empirical case material to argue that it is not simply enough to extend Foucault’s thinking, rather a new way of thinking is required to adequately conceptualize how governance is being operationalised. Such new thinking tends to be well cited because it can generally be applied to making sense of lots of phenomena, such as the governance of schools, hospitals, workplaces, etc. Of course, Foucault consistently operated at this level, which is why he is so often reworked at Levels 2 and 3, and is one of the most impactful academics of his generation (cited nearly 42,000 time in 2013 alone). Writing a Level 4 piece requires a huge amount of skill, knowledge and insight, which is why so few academics work and publish at this level. Such pieces will be accepted into the very top ranked journals.

One way to think about this taxonomy is this: generally, those people who are the biggest names in their discipline, or across disciplines, have a solid body of published Level 3 and Level 4 material — this is why they are so well known; they produce material and ideas that have high transfer utility. Those people who well known within a sub-discipline generally have a body of Level 2 and Level 3 material. Those who are barely known outside of their national context generally have Level 1/2 profiles (and also have relatively small bodies of published work).

In my opinion, the majority of papers being published in international journals are Level 2/borderline 3 with some minor extension/reworking that has limited utility beyond making sense of a specific phenomena, or Level 3/borderline 2 with narrow, timid or uninspiring extension/reworking that constrains the paper’s broader appeal. Strong, bold Level 3 papers that have wider utility beyond the paper’s focus are less common, and Level 4 papers that really push the boundaries of thought and praxis are relatively rare. The majority of articles in national level journals tend to be Level 2; and the majority of book chapters in edited collections are Level 1 or 2. It is not uncommon, in my experience, for authors to think the paper that they have written is category above its real level (which is why they are often so disappointed with editor and referee reviews).

Does this basic taxonomy of impact work in practice?

I’ve not done a detailed empirical study, but can draw on two sources of observations. First, my experience as an editor two international journals (Progress in Human Geography, Dialogues in Human Geography), and for ten years an editor of another (Social and Cultural Geography), and viewing download rates and citational analysis for papers published in those journals. It is clear from such data that the relationship between level and citation generally holds — those papers that push boundaries and provide new thinking tend to be better cited. There are, of course, some exceptions and there are no doubt some Level 4 papers that are quite lowly cited for various reasons (e.g,, their arguments are ahead of their time), but generally the cream rises. Most academics intuitively know this, which is why the most consistent response of referees and editors to submitted papers is to provide feedback that might help shift Level 2/borderline Level 3 papers (which are the most common kind of submission) up to solid Level 3 papers – pieces that provide new ways of thinking and doing and provide fresh perspectives and insights.

Second, by examining my own body of published work. Figure 2 displays the citation rates of all of my published material (books, papers, book chapters) divided into the four levels. There are some temporal effects (such as more recently published work not having had time to be cited) and some outliers (in this case, a textbook and a coffee table book) but the relationship is quite clear, especially when just articles are examined (Figure 3) — the rate of citation increases across levels. (I’ve been fairly brutally honest in categorising my pieces and what’s striking to me personally is proportionally how few Level 3 and 4 pieces I’ve published, which is something for me to work on).

So what does this all mean?

Basically, if you want your work to have impact you should try to write articles that meet Level 3 and 4 criteria — that is, produce novel material that provides new ideas, tools, methods that others can apply in their own studies. Creating such pieces is not easy or straightforward and demands a lot of reading, reflection and thinking, which is why it can be so difficult to get papers accepted into the top journals and the citation distribution curve is so heavily skewed, with a relatively small number of pieces having nearly all the citations (Figure 4 shows the skewing for my papers; my top cited piece has the same number of cites as the 119 pieces with the least number).

In my experience, papers with zero citations are nearly all Level 1 and 2 pieces. That’s not the only kind of papers you should be striving to publish if you want some impact from your work.

Rob Kitchin

Slides for "Urban indicators, city benchmarking, and real-time dashboards" talk

The Programmable City team delivered four papers at the Conference of the Association of American Geographers held in Tampa, April 8-12. Here are the slides for Kitchin, R., Lauriault, T. and McArdle, G. (2014). “Urban indicators, city benchmarking, and real-time dashboards: Knowing and governing cities through open and big data” delivered in the session “Thinking the ‘smart city’: power, politics and networked urbanism II” organized by Taylor Shelton and Alan Wiig. The paper is a work in progress and was the first attempt at presenting work that is presently being written up for submission to a journal. No doubt it’ll evolve over time, but the central argument should hold.