A new Programmable City Working Paper (No. 45) has been published. PDF

Decentering the smart city

Abstract

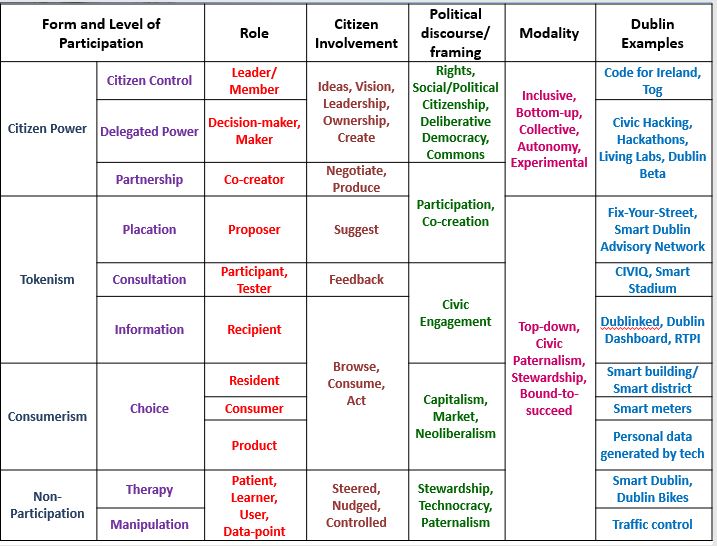

This short working paper provides a critique of the smart city and the alternative visions of its detractors, who seek a more just and equitable city. Drawing parallels with data activism and data justice, it is argued that two main approaches to recasting the smart city are being adopted: inverting the ethos and use of smart city technologies; and discontinuing and blocking their deployment. The case is made for decentring the smart city, moving away from the reification of technologies to frame and consider their work within the wider (re)production of social relations.

Key words: smart city, technological solutionism, decentring, equality, justice, citizenship

It is a pre-print of Kitchin, R. (in press) Afterword: Decentering the smart city. In Flynn, S. (ed) Equality in the City: Imaginaries of the Smart Future. Intellect, Bristol.

The core argument is captured in this passage.

We need to stop casting ‘smartness’ and digital technologies in a privileged, significant independent role and recognize them as the agents of wider structural forces. This requires us to focus on and imagine the future city in a more holistic sense, and how smartness might or might not be a means of realising a fairer, more open and tolerant city. Rather than trying to work out how to insert equality into smartness, instead the focus is squarely on equality and reconfiguring structural relations and figuring out how smart technologies can be used to create equality and equity in conjunction with other kinds of interventions, such as social, economic and environmental policy, collaborative planning, community development, investment packages, multi-stakeholder engagement, and so on.

The issues facing cities are not going to be fixed through technological solutionism, but a multifaceted approach in which technology is one just one component (Morozov and Bria 2018). Homelessness is not going to be fixed with an app; it requires a complex set of interventions of which technology might be one part, along with health care and welfare reform, tackling domestic abuse, and a shift in the underlying logics of the political economy (Eubanks 2017). Congestion is not going to be fixed with intelligent transport systems that seek to optimize traffic flow, but by shifting people from car-based travel to public transit, cycling and walking. Similarly, institutionalized racism channelled and reproduced through predictive policing will not be fixed solely by tinkering with the data and algorithms to make them more robust, transparent and fairer, but by addressing institutionalized racism more generally and the conditions that enable it (Benjamin 2019).

In such a decentred perspective, platform and surveillance capitalism are not framed as separate and distinct forms of capitalism, and racism expressed through smart urbanism is not cut adrift from the structural logics and operations of institutionalized racism (understood in purely technical and legal terms). Rather, smart city technologies and their operations are framed with respect to capitalism and racism per se, and the solutions are anti-capitalist alternatives and anti-racism in which smart city technologies might or might not play some part.

Read more Paper PDF

Rob Kitchin